You should never use jargon for a general audience without first explaining it.

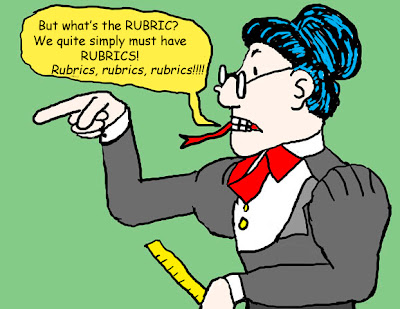

Lately, I've been carping about the ubiquitous (in academia) word "rubric." It's cringeworthy.

Here's a slightly more developed version of my carpage:

The OED:

I consulted the

Oxford English Dictionary, which famously provides the history of words used in the English language.

Evidently, in English, the word “rubric” was first used, circa 1400, to refer to a “

direction in a liturgical book as to how a church service should be conducted…” (OED). Traditionally, these directions were written in red (the word seems to have derived from a French or Middle French word for ocher/ochre).

That initial meaning quickly gave rise to a prominent new meaning of “rubric” as

a “heading” of a section of any book—again, written in red. One hundred and fifty or so years later, the noun “rubric” referred to the heading of a statute in a legal code (the color dimension drops out). By the early 19th Century, the word was used to refer to a “descriptive heading; a designation, a category” (OED).

Let’s call this the “heading/category” sense of the word “rubric.”

Also knocking around in recent centuries is/was a meaning of “rubric” such that it refers to an “established custom” or prescription—this strikes me as diverging significantly from the original textual meaning.

Let’s call this the “rule/prescription” meaning.

Also, “rubric” was used to refer to a “calendar of saints” or the names on such a calendar, written in red.

Evidently, by the mid-20th Century, academics (only in England?) used the term as an “explanatory or prescriptive note introducing an examination paper” (OED). This appears to be a very specialized meaning. Interestingly, it seems to derive from “rubric’s” initial meaning as a “direction,” though the color and religious dimensions are absent.

Meanwhile, back in the colonies:

My Mac’s dictionary

* defines “rubric” as a “heading on a document,” but it also cites the original meaning (see above) and two more meanings: a “statement of purpose” and a “category.”

Merriam-Webster's account of the word starts with the word’s initial meaning: “an authoritative rule; especially: a rule for conduct of a liturgical service….” But it also lists “the title of a statute,” a “category,” a “heading,” an “established rule,” and finally “a guide listing specific criteria for grading or scoring academic papers, projects, or tests.” More on the latter meaning momentarily.

|

| Want rubrics? I'll give yah rubrics |

My own history with the word seems to have brought me in contact with the “category” and “heading” meanings. (“Gosh, doesn’t that investigation belong under the ‘natural philosophy’ rubric?”) Until recently, I had no idea the word is associated with the color red or that it initially referred to directions (in texts, in red) concerning religious rituals. The above lexicographic info does seem to explain why one might have my particular understanding of the word.

* * *

Nowadays, some academics insist on using the word “rubric” or “rubrics” to refer to assessment tools. They're pretty unapologetic about this peculiar conduct of theirs. No doubt, such use of the word makes them feel special, but it tends to confuse the rest of us, including many academics. It seems clear that this particular usage is

new and technical (in some benighted academic circles: education?) and, insofar as it is

imposed on a wider (and bewildered) audience, it is classic “

jargon,” in the most

negative sense of the word. Perhaps the usage derives from the 20th Century usage referred to by the OED: an “explanatory or prescriptive note introducing an examination paper.” But I doubt it. It is a long way from that meaning to the current educationist jargony meaning.

Wikipedia has an interesting article about “Rubric (academic)”:

In education terminology, scoring rubric means "a standard of performance for a defined population". The traditional meanings of the word Rubric stem from "a heading on a document (often written in red—from Latin, rubrica), or a direction for conducting church services". …[T]he term has long been used as medical labels for diseases and procedures. The bridge from medicine to education occurred through the construction of "Standardized Developmental Ratings." These were first defined for writing assessment in the mid-1970s and used to train raters for New York State's Regents Exam in Writing by the late 1970s….

. . .

...Rubric refers to decorative text or instructions in medieval documents that were penned in red ink. In modern education circles, rubrics have recently (and misleadingly) come to refer to an assessment tool. The first usage of the term in this new sense is from the mid 1990s, but scholarly articles from that time do not explain why the term was co-opted….

I briefly investigated the history of this entry. In one of its original iterations, the article stated:

In education jargon, the venerable word rubric has been misappropriated to mean "an assessment tool for communicating expectations of quality." Rubric actually means "a heading written or printed in red" (see main entry for rubric). We may hope that some other term will soon replace the fad for this misuse of rubric.

In educationese, rubrics are supposed to support student self-reflection and self-assessment as well as communication between an assessor and those being assessed. In this new sense, a rubric is a set of criteria and standards typically linked to learning objectives. [Good God, my eyes are glazing over.]....

Well, whatever.

The "technical terms are superior" fallacy:

Over the years, I have often encountered a particular fallacy that is available to those who learn the technical terms of a particular field or discipline. The fallacy is committed when one supposes that one’s technical meaning of word X is somehow the

true and correct meaning of that word; accordingly, one supposes that that meaning eclipses (or should eclipse) the word’s

ordinary meaning (what philosophers call the meanings of “natural language”).

Utter nonsense. In general, the meanings of words in our language do not require repair or adjustment or replacement. (Admittedly, they do require discerning and informed use.) Technical meanings arise relative to particular disciplines and their particular agendas and issues. Thus, for example, there is a very good reason for the technical term “valid” in logic, just as (no doubt) there is a very good reason for the technical term “mass”

** in physics. (I'll stick to logic, which is a discipline within my field.)

Even so, it would be absurd for logicians to advocate (to the broader community) abandoning the ordinary meaning(s) of “valid” in favor of this technical meaning. The most that can be said in favor of the latter meaning is that our language (as English speakers) would be enriched by adding yet another meaning of “valid,” namely, the logician’s technical meaning. But if we seek to continue to speak (and write) well, we need to keep those non-technical meanings in our quiver.

It seems to me that it is exactly those fields that are least secure in their standing (in academia, or among intellectuals) that tend to produce “experts” who insist on imposing their technical meanings on the rest of the population. (SLOs, anyone?)

Education people (or whoever you are): in English, “rubric” means “heading” or “category.” It does not mean “an assessment tool for communicating expectations of quality.”

If you feel that everyone should adopt this particular technical meaning (shoving aside more venerable meanings), you need to make a case.

Good luck with that.

*New Oxford American Dictionary, 2nd Edition

**An argument is

valid, in the logician’s technical sense, if, upon viewing the premises as true and the conclusion as false, a contradiction arises. Physics:

mass is "the quantity of matter that a body contains, as measured by its acceleration under a given force or by the force exerted on it by a gravitational field." --NOAD